|

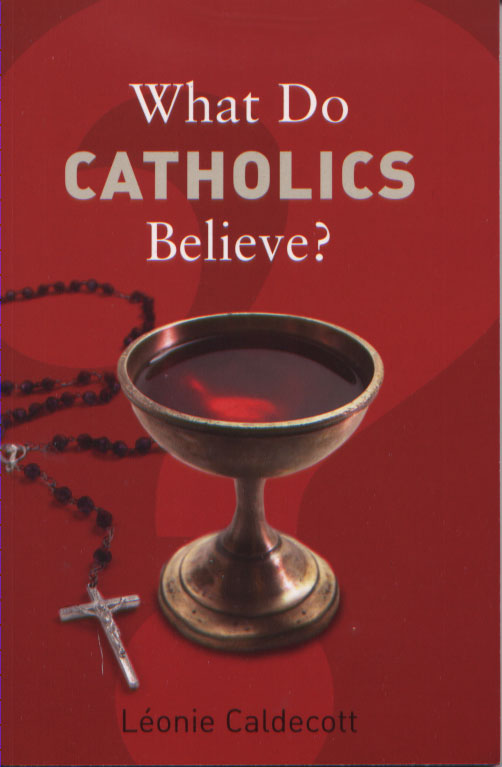

WHAT DO CATHOLICS BELIEVE? Contents Introduction – A Christian Perspective Chapter 1 – The Quality of Mercy: Role of the Sacraments Chapter 2 – No Man is an Island: Last Things and the Communion of Saints Chapter 3 - The Paradox of the Papacy Chapter 4 - Two Thousand Years of History Chapter 5 - “I Make All Things New”: The Church in the World Epilogue - The Conversation Further Reading Index and Glossary

For my father, who first taught me to pray I am all at once what Christ is, ' since

he was what I am, and Gerard Manley Hopkins ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank a number of people who helped me in various ways, through prayer, practical help or constructive criticism, as I wrote this book. First and foremost is my husband, Stratford, without whom I would not have managed to bring this project to fruition at all. Thanks are also due to Tony Morris who entrusted the project to me, and Bella Shand, for her refining editorial hand in the last stages. I would also like to thank, in no particular order, for help both practical and spiritual, Sr Ann Catherine OP, Sr Jane Dominic OP, Adrian Walker, Brigitte and Jonathan and family, Fr Dominic. Finally credit goes to my daughters, Tessa, Sophie and Rosie, whose culinary skills and readiness for lively discussion around the dinner table enhanced the time of my labour. Plaudits for all errors and infelicities that remain go to me. 31st May 2007 Feast of the Visitation Introduction A Christian Perspective From the chilly autumnal night, I step into the softly-lit cathedral. I move up a side aisle, towards the statue of the Virgin Mary. Mass is drawing to a close, and all around me the congregation is gathering into queues, getting ready to receive communion. The church is very full. It is the feast of Our Lady of Walsingham. I fall to my knees in front of the medieval image of the Mother of God, a gift to this nineteenth-century Catholic cathedral from the far more venerable Westminster Abbey. I am not there to receive communion - I have not attended the Mass. Yet my prayer in front of Mary takes on a particular quality: a quality which derives from the present focus of this large body of people. With a startling concreteness, Mary becomes present to me precisely as the human body which first contained that divine body, the body of her son. Mary is the person who, more than any other, is mystically linked to the extraordinary story of God made man. An omnipotent God who elects to be born as a tiny, vulnerable baby from her womb. Living among men, suffering and dying among men. Here, at the culmination of the Mass, is the reality for which all Roman Catholics live: the sharing in that humanity of God incarnate, the participation - through an act as simple as eating - in his divinity. It is the feeding of the five thousand. It is the hordes of hungry souls down the sweep of history. I feel those souls in the souls around me, I am bound up with them. I understand myself as part of the body that is the Church, a body which finds its archetype in Mary, daughter of Zion, who first gave flesh to this paradoxical God whom we long to receive, not just as an abstract idea, but physically, intimately. On the tongue.

Twenty two years before this, I was also in a great cathedral. I was puzzling over the question of faith. My eye was drawn to a sumptuously coloured mural of Christ in glory, sitting in the midst of a mandorla, that opening created by the precise geometry where two circles intersect at each other’s centre. It was the beauty that was holding my attention, yet this attention was not of an intellectual nature. My mind was in a spin, trying to come to grips with a double bind. On one side there were my doubts and fears about the Roman Catholic Church. Issues to do with authority, dogma, freedom of conscience. Fears about terrifying historical associations, crusades, heresy hunters, Borgia Popes. Questions about the cult of saints, and in particular the Virgin Mary, who seemed to me so far removed from the rest of women as to be entirely inaccessible. And yet I could not tear myself away, on account of one thing. That tiny host, that wafer of bread, which Catholics receive at the end of Mass when they go to communion, believing that it has become the Body of Christ. Not symbolically, metaphorically: but literally. At a particular moment in the Mass, called the consecration, Catholics believe this piece of wafer-thin bread becomes Christ himself. “Take this and eat it, this is my body which will be given up for you,” he said at the Last Supper. “Do this in memory of me.” This is the heart the matter: it is for this that I became a Catholic. In spite of my confusion, I knew I had to receive communion in order to be fed. It was that simple. The word Eucharist, which expresses this transformation of simple matter into the self and substance of God, is derived from the Greek word for thanksgiving. In the end, it was my thanksgiving for what I received that motivated me to try and understand the context of the gift. Just as you do with an incredibly thoughtful birthday present, which expresses perfectly the love that the giver has for you. *** It never ceases to amaze me that in the modern, secularised world people are still fascinated by religion, in spite of attacks made on it by critics such as Richard Dawkins. Religion is a way of seeing, of being, of perceiving reality. Images can sum this up for us, striking though our ordinary life to some deeper level. An exultant goddess in a richly decorated Hindu painting. Jews at the wailing wall, rocking to and fro as they repeat the beautiful phrases of the Hebrew scriptures. The beatific face of the Bodhisattva as he sits in meditation, a giant statue adorning a cliff-face in a remote part of Asia. The compelling eyes of the Mother of God in a Russian Orthodox church, her child encircling her neck with his hand as she looks across at you through a sea of candles and the deep harmonies of the eastern liturgy. The sight of Muslims at prayer in the dappled light of a mosque, all inclined towards the same focal point, unshod and abandoned to their devotion. Sufis turning as their robes billow out to make that perfect circle around the still point which every heart yearns after. Our desire to be in communion with something beyond ourselves – the experience of that mysterious contact - is found in testimonies in every culture and time. ‘Mysterious’ does not mean ‘irrational’: reason plays a considerable role in the belief-system you will read about in this book. For Catholics, reason is essential in unpacking faith. But without the content of faith, the lived encounter with that Other which lies at the heart of our religious practice, reason would be redundant, a machine snapping at empty air. We have to make use of both faith and reason in explaining what Catholics believe. These are two sides of the same coin: complementary aspects of human experience, right-brain function in precisely calibrated balance with left-brain function. On the one hand, there is the voice which adumbrates the structure, the rational belief system, which gives us access to the faith; and then, there is the voice which speaks of the heart, the lived experience of that faith. In recent years there have been moves in theological circles to bring theology, as an intellectual reflection on faith and Scripture, back into contact with spirituality again. This has been called doing theology on your knees. It’s about time. *** There is a statue which stands over the door of my parish church, a statue of Jesus as the Good Shepherd. He stands there, watching people go in and out. His face wears a smile, his body stands in a relaxed position, hoisting a lamb on his shoulders. With his right hand he holds the lamb’s feet to keep it steady. With his left hand he grasps a shepherd’s crook. But it is the expression on the face of the lamb which fascinates me most. The lamb has no intention of falling off those shoulders: he is pressed against that neck as though he were aspiring to become a part of it. His face is blissful. He looks down at you just as the shepherd does. And that’s the point: he’s in the perfect position to see everything from the point of view of the person who carries him up there on his shoulders. He has perspective. For me, this image expresses something crucial about Christianity. At its heart is something which goes beyond doctrinal arguments or moral conundrums. It is an invitation not simply to believe in Christ, but to be lifted up to his level, to try and share his perspective on ourselves and those around us. This is an interior thing, of course, and we don’t manage it most of the time. But Christianity is void and useless without this possibility, since it is this close relationship with the God made man which makes us more than just Sunday pew-fillers. The Christian religion is first and foremost about relationship, beginning with the relationship between God and man. The first place we have to look to understand this relationship is sacred scripture. One of the most famous of the Jewish scriptures, found in what Christians call the Old Testament, is the book of Genesis, which recounts the creation of the world. Catholics think of such texts as allegorical or symbolic – even in the fourth century St Augustine knew that the world was not created in seven days, as we think of time. This does not mean that these scriptures are not profoundly true. Written under the influence of divine inspiration, even the most ancient of these texts describes our relationship with God. Thus in Genesis it is written that God entered into a covenant with Abraham, which means a freely chosen undertaking on the part of one person towards another. The essence of this covenant was God’s promise to bless Abraham’s descendants and make them more numerous than the stars. Through that relationship, and the inspiration that God gave to the prophets and authors of the Bible who descended from Abraham, the divine nature was revealed in a special way. God was more than just a tribal deity. He was God of the whole universe, and the maker of all that is, but at the same time he was a God who wanted to be with his people, in their very midst. To be understood, God’s decision has to be set against the background of the Fall, described in the second chapter of Genesis. There we find the aboriginal story of mankind’s first parents, Adam and Eve. They disobeyed God’s order that they should not eat the fruit of a certain tree in the garden of Eden - the “the tree of the knowledge of good and evil”. Eve gave in to the temptation of the serpent, who told her that if she and her husband tasted the fruit they would ‘become as gods’. She plucked and ate the fruit, and persuaded Adam to do the same. This abuse of human freedom (for God is portrayed as commanding but not compelling) is called Original Sin. It resulted in the Fall, that is to say a breakdown in communion between man and God, and mankind’s expulsion from Eden. The rest of the Old Testament relates how God tried to repair the breach through one particular people, the Israelites, descendants of Abraham. The Christian New Testament goes one step further. It shows God taking the covenant that he had made with the Jewish people, and opening it up to everyone, creating a universal religion. He does this in an unprecedented way, not simply by speaking through another prophet, but by taking on human nature – a body and soul like ours - in order to reveal himself as fully as possible to us, in a language we can all understand, whatever race or tribe we belong to. “For as a by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Corinthians 15: 21-22). Christians believe that God effectively sent a ‘second Adam’ to redeem the fault of the first one: he sent his own son, Jesus Christ. The life of Christ is recorded in the Gospels, four documents written after Jesus’ death and forming the core scripture of Christianity. Jesus was crucified by the Romans at the instigation of the Jewish authorities, essentially for blasphemy (that is, for implying or claiming that he was equal to God). He voluntarily accepted this terrible death as a way of taking on himself the consequences of human alienation from God. But he rose from the dead and ascended into heaven, proving that death no longer had any power over him, and promised eternal life to anyone who would join themselves to him in faith, hope and love. Christians believe that what Jesus reveals to us is both Man and God. He revealed the nature of God as love. The central message of the Gospels is that only in loving God and each other can we find our own ultimate fulfilment and meaning. This characterises the way prayer is experienced by the Christian. It is the God who lifts us up on his shoulders who makes us capable of prayer. And “prayer” does not refer only to verbal communication. Perhaps the simplest definition is “turning the mind and the heart towards God”. A kind of pure attentiveness. For a Christian, prayer is the joint work of God and the human being, for our spiritual or interior life depends on a profound cooperation with God. On our own we can question and praise and ask, but only the presence of God makes these interior actions into a real communication with him, which gives us the possibility of seeing things from a divine perspective.

|