|

The New Journey to God by Catherine Dalzell

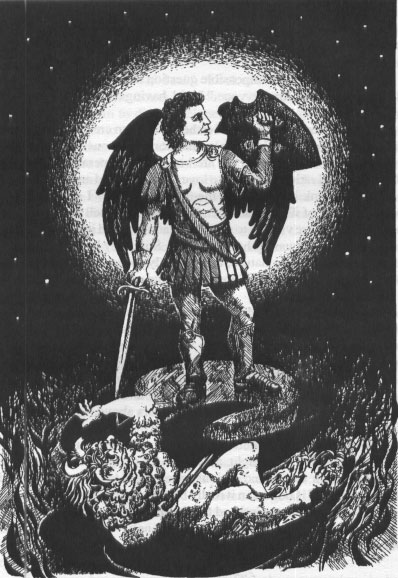

Chapter 4 November 11, 1993 Continued In which St. Michael is asked about the fall of Satan and the war in Heaven. Catherine learns about a Franciscan venture and begins to read the Mind's Journey to God. WE LEFT THE MEMORIAL and turned to pass under the Hart House Tower. The tower itself straddles a foot path, so one can pass directly from the campus to the sports grounds and to Hoskin Avenue to the north. On the walls beneath the tower there are more names, the fallen in a second conflict, one side surmounted by a relief image of St. George, and the other with St. Michael, complete with wings, shield and serpent. I pointed to Michael's image and the wall of names. "Does it not bother you to be associated with this kind of thing?" I asked. "I mean, it is a bit militaristic." "So am I," replied Michael. "But I thought you were a Christian of some kind," I said. "Aren't you supposed to be against war and suffering?" "I am for God," he said. "But as to war, do you think it would be better if the aggressive always took what they wanted, and wanted what they could take?" "I guess not," I said. "But would it not be better to have an international government, where that sort of thing could be policed?" "Certainly, if your international government is just, and has the support of the people. But remember that a policeman is only a soldier by another name. You will still be using force to repel force, and your moral dilemma will be the same." Michael stared gravely at the names on the wall. More people that he knew, I assumed. "Does it make you sad to think about their lives?" I asked. "Who is like God? I am not as great as that," he said. And I had to admit that neither grief nor resignation seemed able to touch that calm and balanced face. "I am among the blessed," he added, in a tone that sounded quite the reverse. "I neither share your condition, nor know your sorrow. I cannot prevent moral evil or turn it into good. You see, I am not so different from the fallen that you honour today." "You make it sound useless," I said. "But they won, and surely you have never lost." "It depends on what you mean by winning," he said. "War is at best the attempt of that which is still good to defend itself from evil. We establish a barrier between the aggressor and his intended victim in the hope of protecting for a time the good that remains. All the laws and the armies that enforce them ultimately do no more than that. We gain a few years, protect a few happy lives; then the evil shifts and we move the barrier somewhere else. God made the seraphim for love, and yet the icons depict me as a soldier. Faced with evil, natural love can do no more. It was in part to show my weakness that I chose to be depicted in that way." We walked through the arch. I thought of Milton, and the many pictures of St. Michael as the warrior archangel. These were not to my mind pictures of weakness.

"Does Satan exist, and did he really fall from Heaven?"

"Michael," I said, "are the stories true? Does Satan exist, and did he really fall from Heaven?" "He did not," said Michael, grimly. "In the power of the Lord I threw him out. And 'out' is where he is going to stay." "What happened exactly?" I asked. There was a long pause. Michael repossessed his umbrella and held it above the two of us. Then looking straight ahead, as if addressing someone else, he began his story. "In the beginning God laid the foundations of matter and created the heavenly host. He made nine choirs in all, three groups of three, much like your military. It is our task to reflect God's glory and implement his designs in creation. "What do the different choirs do?" I asked. "It is a complicated system, but in general, the first choir reflects the primary attributes of God in created form: the seraphim are for love, the cherubim for truth, and the thrones represent his governance: what you might call majesty or peace." "Are the thrones in charge?" I asked. "No. We are — the seraphim — since it is love that gives direction to everything else, including government and truth. The middle group, the dominions, virtues and powers, are mainly deployed in directing the physical and biological realms. And the last group concerns you. These are the principalities, archangels and angels. It emerged that they would direct the human race, both as individuals, and in their nations, institutions and culture. "In the beginning we had no idea what a man would look like, or how the parts would fit together. We knew that you would be bound by the world we were to direct, and yet be rational spirits like ourselves. Frankly, it sounded like a contradiction in motion, but since it looked as if you would only be the concern of the lower ranks, I for one did not give the issue much thought. "To understand what happened next, you have to realize that when we were first created, we did not know God as we do now. We knew ourselves in a kind of a way, and we knew the existence of God, but we did not see him face to face. He communicated to us through the signs of our language, and we knew him as that which sustained everything that we could see. It was like being half a person, without even the knowledge of the whole; I had as yet no name, and I did not notice the lack. "As a seraph, I knew that I was made to be an image of God's love. I knew this because he had written it into my nature, but I did not know what love was. It is not that I had an explicit theory that later turned out to be wrong, but I simply assumed that love was no more than what I had already seen it to be: creating, designing and sustaining. I knew that God loved me, and I knew that I loved the universe that I was asked to shape, but that was it. To me love was work, the power of adding value. The others would tell you similar stories. It was all perfectly innocent, but terribly limited. "This state of affairs was not allowed to persist. On the evening of the first day God told us that he intended to inhabit the universe he had made and become man. The First to exist would become the last thing made, and all things would serve him, not only in his glory, but also in his need. The air would fill his lungs, the water would quench his thirst, and the pure spirits would guard the footsteps of the One who governs history. "It makes sense when you think about it, but at the time I was amazed. What could God do for man as man that he could not do more efficiently as God? It flew in the face of everything I knew about love. I turned to God in confusion to ask what this could mean, but for the first time it seemed to me that he was not there, and that I was alone." "And the heavens were silent for one hour," I quoted. "That must have been horrible." "Horrible? No. I was sure that if he intended to lower himself to man's level, then this too must be love. No. The horror came later. "I don't know what happened next, whether it was something that I saw or something that I was told, but suddenly I realized that love does not mean simply building vast projects for others, not even projects for God, however glittering. I realized that to love is to serve, and that in becoming man, God would give his creatures a greater gift than life itself, namely the opportunity to serve the One who needs no service from us. "Then the blinds fell from my eyes, and I looked on the face of the Most High. I saw, as I see now, the three in one, and the one in three. And I adored him ... "My next thought was to relate all of this to Lucifer, since we shared everything we knew. Then I received my second surprise for the day. To begin with, he had no interest in what I was saying. I don't even think that he heard me. Then when I looked more closely, I noticed something very odd. He seemed to be turned back on himself, curled up in a tiny ball. And then, instead of directing his thoughts outward, which is the normal form of angelic thought, he looked as if he was trying to swallow the universe and pull the whole thing back into himself. And he kept muttering over and over to himself, 'I shall be like God, I shall be like God, I shall be like God.' "I did not know what to do or what to think. We did not even have a word for this ... refusal of a creature to be a creature. I saw God in his eternal self-giving, I saw the brilliant world he had planned, and how each thing in it retells in its fashion the love at the foundation of the world. And then I saw my friend all rolled up, a miserable abortion of the rational spirit, hating all that loveliness. "It made no sense. What I saw, what was quivering and raging before me, could not exist, could not make sense — and yet it was there: unthinkable, impossible, and still there." Michael paused for a moment, and I tried to imagine what it would be like to see evil for the first time. "What did you do then?" I asked. "I vigorously and spontaneously ejected the experience from memory." I thought of someone throwing up in the presence of an atrocity. It was not an heroic image and I tried hard to suppress it. "It was not an heroic

moment," said Michael blankly. "How could it

be? Evil is a poison, not a problem, and it is seldom helpful to look at it. But there was more to follow. On that day it seemed that truth itself must die. The lines of corruption began to propagate from the centre of the catastrophe. Everyone else was equally stunned, but to my growing horror, I noticed that some of the others were rolling inward as "Then I heard the voice of the Lord, stronger and more beautiful than I had ever known it. 'What will you choose?' he asked. I said, 'I will serve.' Then he told me to rally my associates, and I did that." "What did you tell them to sway their minds?" I asked. "I told them nothing. That was the whole difficulty: they were listening to other angels when they should have turned to God if they had doubts. I said only, 'Who is like God?' to remind them of who it was who had given them their existence and their understanding. The less they thought of Lucifer, or myself, or themselves, the better. The question took effect. Two thirds of the host rallied to the Lord's standard. As for me, the name stuck and I have been Mi'kha'el ever since, which means 'who is like God?' "That was how it began; but of course, it didn't stop there. Hatred never does. The war might have continued for ever, but in the power of God, we expelled the enemy and the spirits that followed him " We stopped for the light at Hoskin Avenue, and stood facing the elegant, Gothic frontage of Trinity College, the university's Anglican establishment. I tried to picture the war in heaven, but failed. It must have been a battle of titans, engaging forces more powerful than any found in nature, and yet from Michael's description, it sounded like a fight among children totally unptepared for the sight of evil. It must have been both very petty and very horrible. "What do you think went wrong?" I asked. "I do not know," he replied. "You could go mad trying to understand evil, and still not be any wiser." "But you figured out what God intended. Why couldn't he?" "I figured nothing," the archangel replied. "There is infinitely more to God's love than I imagined at the time. When I saw him, I knew, and knew also that I would never see through the depths of it." But I did not want to give up as easily as that. "Do you think there was something wrong with Lucifer from the start? Or that he was stupid in some way?" "Not at all. He was created to be good and there was no flaw there, nor did God will his error. As to intelligence, if that were an issue, what human could be saved? Hell contains exactly the same sort of people as does Heaven, considered from the standpoint of their natural gifts. The only difference between them is that the citizens of Heaven choose love while the damned choose not." But Michael's story raised the mystery of created, freedom, and I could not believe that even he was incapable of understanding it. "When was the moment that you actually decided for God?" I asked. "Was it when he left you alone?" "I never said that he left me alone; only that it felt as if I were being left alone. Later I realized that he had only withdrawn a created symbol of his presence. It was like the moment of dusk, when you can no longer see the land clearly, but the sky is still too bright for the stars to appear. Someone trying to navigate by familiar signs would have difficulty both when looking for the daytime landmarks and when seeking direction from the North star. At first, we only had the daytime knowledge. We knew created things in a natural way, and we knew God as that which was beyond them and guaranteed their presence. But he wanted us also to know him face to face and, taking God as our starting point, to know all things in him, including ourselves of course. "Don't imagine that I stood at some imaginary crossroad, with the road to evil in one direction, and the road to good in another. To see evil as a viable option, as one course of action among others, is already to have the mentality of a fallen race. I never ceased to trust in God. There was a moment when I knew that I was, in a sense, stepping outside of myself, and reaching for the God that lives beyond my capacities to grasp his ways; but it was his grace that moved my heart to him, so that at no time have I been as free as I was then, or as completely his." "So if Lucifer and the others had not chosen against God, you might never have known the extent of your freedom," I suggested, as the mystery of Providence compounded the mystery of freedom. "Never say that!" he said quickly. "God would have shown us the extent of his gifts by other means. You can see from your own experience that whenever you learn from evil, it is not error itself that is your teacher, but the truth in which you recognize the evil for what it is." "It seems then", I said, "that you too are saved by faith, and that faith comes through grace." "Yes," he said. "And from grace, glory." We crossed the road and sat down on the stone wall that separates the college lawn from the street. I was still struggling with the problem of grace and free will, and it was a relief not to have to struggle with the rain, the umbrella and my own two feet as well. "Ultimately, " he said, "the mystery of grace rests on the mystery of creation itself. you cannot grasp the time, the place, or the action whereby your spirit is sustained by God. Your being and hence your freedom are not powers that you own and can comprehend. Their origin is in God. It is through the Word that we are made, and through the Word that we are brought into communion with God. "The world around you, the books you read, your friends, my words even — all these can influence your decisions from the outside. But only God can move the heart from the inside, so that you can love with His love." "But if God is moving my heart, how can I say that I am free?" I asked. "You are free because the actions are yours, and the love is yours. You have them as a gift, but once given, they are yours. In that sense you are free. But you are much more than free; we discussed earlier how the mind is a mirror of the Trinity through its natural powers of thought, but where the mind is transformed by grace, the Trinity is reflected within the soul itself. If you could only see the beauty of it ..." But I could not. "What does it mean, precisely, to have the Trinity reflected inside oneself," I asked. "It means that you are in Love," he replied. A few weeks earlier I had visited the recently purchased home of a newlywed friend. It was beautiful to see: a little world, complete, for a moment at least. And happiness is not so common in this world that I could have the heart to envy what she had. I did not have the foundations for a family of my own; and that was it. Michael reminded me of her: if one could only have the love that he enjoyed. There was no room for envy; I was unclean and unworthy. "In the case of mankind," continued Michael, "the word of grace is also a word of atonement and reparation — another amazing act of love!" And he laughed with delight. "Were you surprised by that too?" I asked. "We never cease to be astonished by the Lord. When we expelled Satan from Heaven, I assumed that would be the end of it. I even expected that God would unmake him, but I was mistaken. God never takes back his word and he had given us the word of immortality. "At first, we heard nothing from Hell. The enemy seemed to have disappeared. But it soon became apparent that Satan had not abandoned his hatred for God, and since he could no longer storm Heaven, he began to wreak havoc in material creation. We were given to understand that he would make an attempt against your race, when it would appear. "When your race was seduced, we assumed at first that you would also be reprobate like the demons, and that the Incarnation project would be abandoned. We were amazed when we learned that the Word would become a member of an impure species. How little did we know of the depth of his love!" His face was radiant with joy as he said this and I turned away in shame at what I was. "Regret nothing," he said. "Evil turned the world inside out, but love has turned it upside down. In Love's new law, the greater serve the lesser — even in unimportant cases. For instance, when Satan decided to break ranks with the seraphim and directly influence the course of human history, I was asked to volunteer as an archangel and lead the third choir in the battles that were ahead. I was told that if one had fallen, another must descend by choice. "But I am far too small to descend as far as he has done, and you who share his body share more deeply in the world's redemption. I remember when I served as guardian angel to Jesus. Those were difficult years, because most of the time I had to stand by and do nothing. I could have saved him the death and the humiliation; I could have prevented the Jews, whom I love, from their disastrous choice. Everything in nature appealed to me to oppose these evils, but Love appealed that I stand and watch." Michael fell silent. "Were you there when he was crucified?" I said at last. "Yes, I was there. Of course I was there. And I had twelve legions of angels with me, waiting in case a signal came to act. Not that I expected it. We knew the Messiah was to suffer; there were the prophecies and his own words. But a guardian angel has certain responsibilities. "She was there too. I stood beside Our Lady as she took all the world's sorrow into her heart. I would have done anything for her," he said simply. "She is the one who trampled the serpent under foot. Although all victory comes from God." "I am sure that you were very useful." I said. "Had you not been there, able to prevent it, the Lord's death would not have been the free sacrifice that it was. We would have been left wondering if things had somehow got out of hand." Michael looked startled for a moment and then smiled indulgently. "Thank you for your compassion, but there is no need of it! There is nothing here to comfort. I was happy then as always." "Surely you must have felt some grief," I said. Michael thought for a moment before conceding, "It goes entirely against nature for the creature to kill his creator. What could possibly be worse? They didn't know, of course, but it was difficult to watch. It was all so totally wrong. "But I am telling you this to make you happy, so that you will know that you are now closer to him in your frailty and your mortality than we are in our strength. Suffering, loneliness, poverty, humiliation and death: you need fear them no more, since they bring you closer to him."

THE ARCHANGEL JUMPED DOWN FROM THE WALL. "I want to show you something," he said suddenly, and we set off down the road. We had not far to go, before he turned into the walk leading to the newly restored chapel of Saint Bonaventure. I had not seen it under the new management, but I had heard a lot about it. The university chapel had gone through difficult times — no less trying for being self-inflicted. The intentions were good; no one could deny that church attendance was low among undergraduates. And clearly young people who have lacked something in the parishes of their youth are unlikely to be attracted by a repetition of whatever failed them in the suburbs. To this everyone agreed. However, when it came to the numerous changes to decor and to liturgy introduced in the name of youth relevance, opinions differed. It was estimated that each new change brought an immediate drop by ten percent of the congregation, whatever the nature of the change. After ten years during which the traditions of the faithful repeatedly met with the shock of the new, the regular congregation was down to five people, none of whom were students. Financial bankruptcy is embarrassing under any circumstances, but bankruptcy in the Church attracts suspicion of spiritual bankruptcy as well. This is much harder to live down. Concerned on both counts, the archbishop resolved to act. First, he padlocked the chapel. He assigned the chaplain to a home for the elderly, under the assumption that old people can appreciate new things, and cast about for something a bit more conservative for the youth. After a suitable lapse of time, he brought in the Franciscans. He reminded them that Christ had called upon Francis to rebuild the Church: he spoke a few words on the virtue of simplicity and the danger of intellectual fads; and finally provided a generous budget for restoring the chapel, a budget tied to the sole condition that it must be entirely spent within six months, after which there would be no more money for changes. Shortly afterwards, the chapel was reconsecrated to St. Bonaventure. The Franciscans went to work. They hired a team of artists and builders to restore the interior. While work was in progress, they took over the Newman Centre next door, where they said Mass at useful times of day. They opened a soup kitchen for the poor, and engaged whatever students they could find to run it. They hung bird feeders from the branches of the trees by the chapel and placed a feeding trough on the lawn, so that the squirrels would not be neglected either. Attendance increased. Finally, the restorations were complete. I had been curious about them, in a vague sort of way, but since I usually worshipped at the Cathedral, I had not had a chance to see them for myself. "The door will probably be locked," I said, "and we won't be able to get in." "A real house of prayer is never closed," Michael said as he pushed open the door. Right enough, it was unlocked, and there was more: the Blessed Sacrament was exposed on the main altar and several people were praying. The chapel was not very large, but it had been designed to have a side altar as well as a chancel and nave. You enter from the side of the building, and there immediately to your left, is a small altar bearing the Tabernacle, with a few kneelers in front. Looking straight ahead, you are looking across the nave, and the main altar is also to the left, but beyond the small one. At least, that was the layout that the architect had intended, but under the previous regime, the main altar could be found in any one of several locations, and you never knew where to look. Now the original plan had been restored. We entered and knelt briefly before the monstrance on the main altar. There were two men standing there, one on either side of the altar. One carried a sword, and the other held a censor, which he swung gently to make the incense rise. They stiffened slightly as Michael came in, and he nodded in their direction. "What are they doing here?" I whispered. "I always post two men by the Blessed Sacrament. They guard the Host and the prayers of the faithful." "I never saw them before." I said. "Do you not find it easier to pray in his presence than at home?" I nodded. There is something about a church that makes the inside seem larger than the outside. "That is because he is present. And to make the place worthy of our King and your Saviour, we keep your tormentors quiet and assist your prayers." "Will they always be here?" I asked. "No," he replied. "Only for as long as the building stands, and the Sacrament is reserved." Michael approached the two spirits for some purpose of his own, and I wandered to the back of the chapel. In most churches this would have contained the main entrance and a vestibule leading in from the street. Here, for reasons of space, one entered by the side, and the back wall was free of entrances. The upper two thirds of the wall was stained glass, tiny lozenges of colour with no particular design. A book table ran below the window, and there were two statues at either end, each with a stand of votive lights. Clearly, the one on the left was St. Francis. He stood with arms outstretched, preaching to the birds placed by the artist on his shoulders and by his feet. The other statue represented a Franciscan that I did not know. The figure was angled so that the slim and elegant face was looking towards Francis. He held a script in one hand, and a pen in the other, which he chewed in thought. A cardinal's hat rested forgotten at his feet, while he seemed to consider how to transcribe for a more skeptical audience the sermon that his master was giving to the birds. I looked more closely and saw that a small card had been placed at the base of the figure.

So this was St. Bonaventure, the "other Medieval theologian," the one who was not St. Thomas Aquinas; the one whose opinions are never mentioned except by way of comparison with the Dominican, and even then, seldom with approval. I glanced over the book table. There, between the booklets on making felt banners, and copies of recent social encyclicals, I spotted a small volume, attractively bound in blue and yellow, written by the saint himself. The Mind's Journey to God, it read and underneath, in smaller letters, Itinerarium Mentis in Deum. I picked up the book and began to read where it fell open.

I shut the book and returned it to the table. The other stained glass windows, the ones along the sides and behind the altar, had been removed and replaced by plain glass, so that the interior would be illuminated by natural light. It was not to the windows that we were to look for interest — they were made only for light — but rather to six medallions painted along the walls, three on each side, and to the mural behind the altar The mural was the easiest to understand. It showed an artist's impression of the origins and scope of the Franciscan Order as it was received into the mind of St. Bonaventure, and reorganized under his direction. Bonaventure himself was shown in the foreground, seated at a writing table, with a small crucifix on the desk before him. Up and to the left, like a light shining behind the saint and illuminating his work, was the figure of St. Francis, at prayer on Mount La Verna. The six-winged seraph, in the form of the Cross, had just appeared to impose the stigmata. The painting as a whole was structured according to a great spiral, whose arm began with Francis, plunged downwards to St. Bonaventure, and then swept on up and around in a stream of small pictures showing the work of Franciscans in future centuries. There were brothers in pairs, begging and preaching in the market places; and then further on, more Franciscans teaching at universities. Others were tending the sick and the poor, while scientific Franciscans were experimenting with gun powder and lenses. Then, as the spiral arm plunged into the centre of the picture, perspective's vanishing point, the tiny figures disappeared into the jungles of the Amazon, where mission churches stood beside great cataracts of water. The six medallions were smaller and simpler. They were also more difficult to understand. Each was circular, perhaps one meter in diameter and set in a golden ring. They were painted in pairs, facing each other across the nave, each being in some way matched to the medallion on the opposite wall. On my left as I sat in the rear of the chapel, the first one showed a romantic seascape, where a dark and tormented ocean lashed a rocky coast. There was a low rock in the foreground, and a book lay open on it. The opposite medallion looked as if it might have been a preparatory sketch for the first one. For while the seascape was all masses of colour and light, this one was all line and movement; the first was an oil, and this was a pen and ink drawing of the swirls of the clouds and the eddies of the seas, washed over in yellow watercolour. And yet, despite all differences of medium, some similarity of form united the two. The third and fourth medallions each showed a city. The third, on my left, was a stylized eighteenth-century port. A great sailing ship entered between the quays, where knots of people stood talking and doing business. But if the first city was all sea and sky, the second was all light and gold. I thought of the Book of Revelations, since here was a new Heaven and a new Earth, and there was no more sea. Where there had been water in the first city, here rose in ranks the castellated turrets of a city of gold, vanishing into the clouds, where they mingled with the figures of angels. And yet, the foreground of this picture belonged to a highly realistic style of art. There was a fountain in a square; the paving stones were drawn with care, and there were chips and cracks in the basin of the fountain. A woman was seated on the rim with an open book on her lap, and a group of children had gathered around Again, they looked like real children. Their attention was dispersed; some looked ragged and poor, while others came well dressed and equipped with small games. In contrast, the remaining two panels were starkly simple. The fifth was framed by two cherubim bent in prayer. Between them was a representation of the burning bush, surmounted by the tetragrammaton in black letters, against a green background. The sixth had the same cherubim, this time kneeling before an icon of the Trinity in blue and gold. This was what I saw when I first looked: three disconnected pairs. But as I studied them more closely, I began to see connections between all six, as if the same scene had been painted in six different ways. For instance, the outline of that building in the third panel looked a lot like the rocky cliff from the first; and the curve of the angel's wing in the fifth resembled the sweep of the turrets in the fourth. And having seen that far into the group, I grew increasingly absorbed trying to match up, image by image, each picture with the rest. "What do you think?" asked Michael, now seated on the chair next to mine "It is the most extraordinary thing I have ever seen." I said. "It combines the passion of Turner with the symbolism of the Middle Ages; it is a summary of every artistic insight of the past seven centuries, and it all holds together. Everything is there, and nothing has been lost. But what does it all mean?" "The six medallions signify the six steps of illumination which start with created things and lead to God himself, to whom no one approaches except through the crucified one." Michael replied smoothly. "You opened that book on purpose, so that I would read those words!" "You would have read that book sooner or later. The point is, what did it mean to you?' "I don't know," I said. "Were you the six-winged seraph?" "I was. At least, I was the seraph that Francis saw, not that it matters. What matters is what it meant to Bonaventure, who wrote the book these pictures are attempting to illustrate. "As a Franciscan, Bonaventure wanted to love God in the same way that Francis did. He reflected on what was the culminating moment of Francis' life of prayer — at least its most vivid external sign — and that was the day that Francis received the stigmata in a vision showing a seraph with six wings in the form of a crucifix. Bonaventure realized that, although Christ crucified was the means and the goal of his love, the wings supporting the crucifix must indicate the supports of this love. He argued that these supports must all be different aspects of ordinary creation. You are born in the frontier, so that is where your prayer begins." I looked at the six medallions and wondered. The first three did not seem very religious, and the fourth was a complete mystery. "But what are these pictures about?" I asked. "They are pictures of God," he said. "The fourth panel, the one showing the golden city, is the key to the series." "In that case, I must know very little about God, " I said, "because to me the fourth one makes even less sense than the others." "It represents the human soul restored by grace," he said. "Alternatively, you could take it to represent the Church. The City is the New Jerusalem. still incomplete as you can see, but it reaches into Heaven, since Heaven is its pattern and its home. The book is Scripture, and the fountain represents the waters of baptism." "I thought you said it was a picture of God," I said. "And so it is. The soul restored by grace is like a portrait of the Trinity; she resembles her God because she lives by his life, and loves with his love; and he lives in her. Every man tends to resemble what he loves, and since the soul restored loves God more than herself, should you be surprised that she should resemble her beloved?"

The anxiety is inescapable, nourished by the seeming hopelessness of it all. To be sure, there have always been saints — people who loved God more than themselves, and did reckless things to prove it — but for me, for most of us perhaps, Christianity is too difficult. The promises were not made for us; no one expects great things from us; nor could it ever matter if we finish the race or not. I sat for a moment in silence and wondered how much of this I could convey to a creature who knew nothing but bliss, and who accomplished without effort all that was asked of him "Catherine," he said. "What are you thinking?" The voice seemed almost to be speaking to me from inside my head, as the archangel's outward form remained fixed on the Presence on the altar. Grief condensed into speech, and finally I said, "I do not love God. I have tried, and I just can't do it." "By yourself, no, you cannot. But in his love, and through him, even we who are nothing can love like God." I looked away. What was the use in discussing the impossible and the hopeless? "Catherine!" said the archangel sharply, "how dare you lose hope in what the Lord has promised you: his own Spirit, the same that moves his own heart to love the Father." "I just don't feel anything," I said. "Ah! Feelings! If you are only interested in feelings ... ," he said. "But there are degrees of love. The soul loves God to the extent that she knows him; and her knowledge exists in the same mode as her love for him. For example, how large a sum of money would it take for you to deny the truth of Pythagoras' Theorem?" "I would not deny it for any amount," I said. "It would be ridiculous." "So there you are: an instance of love of God, albeit a distant love, since the knowledge of God that is implied through the truths of mathematics is a distant one. This stage is illustrated by the second medallion. It illustrates the vestige of the Trinity seen in human modes of perception: art, mathematics, reason and the senses." "And the first one?" I asked. "Is that God seen through creation?" "Yes. The book on the rock is the book of nature. I have known many people who returned to God as a result of contemplating nature. Art can also be a draw. I knew a man who was brought to the Church through a love of church music; and another who regained his childhood faith when he asked himself why modern art is so ugly. He concluded that if the art of a godless society had neither form nor beauty, then atheism cannot be true. Unconsciously, he expected to see God through beauty, and where beauty was absent, he rejected the art, and the ideology that inspired it." "I did not think that being an art lover was much use against the powers of Hell," I said. "Artists and scientists can be very selfish." "True enough. Art and nature are too far from God for love of them to save a soul. Their value is rather in preparing souls to accept him. But if they did not resemble God in some fashion, they could not even do that much. "Sometimes the conversion begins elsewhere and then extends to the natural world, as sanctification runs its course. I have known people to go through life almost as in a dream, who, after conversion to Christ, begin to notice the natural world for the first time. Out of love for God, they learn to take creation seriously. But I need hardly explain that to you. The technological superiority of Christendom should be proof enough that love of nature is one effect of love of God. "The third medallion represents God in natural human activity. This is the lowest love of God that has any power to save. Those who lack the knowledge of Christ can still be saved by loving their brothers in accordance with right reason." "I thought no one could be saved without grace," I put in. "They cannot, and neither can they love their neighbour without it. "There is something I do not understand here," I said. "Why is it that love of neighbour should be so important for salvation, but love of nature is an optional extra. Man and beast are equally created beings?" "But they are not created equal," said Michael. "Man exists for God directly; so what you do to help a friend is done for God. You may have noticed that many people develop a lively interest in politics and social justice following conversion. They know that God is to be found through these activities, and they look for him there. "Now here, at the fourth stage, the soul becomes actively like God. Before, it was a question simply of recognizing the divine activity, but here, the soul itself becomes a second Christ and lives from his life. This is where apostolic activity begins, since the Christian who lives the faith will draw others to it. They will see God in him and be attracted. You will have noticed how people can be drawn to the Church by the life of a saint. They fall in love with the saint, but it is God whom they love in that person. Others seem to fall in love with the Church herself. They are fascinated by her structures and her cultural achievements through the course of history. This too can be love of God." He paused to let this sink in, while I studied the paintings with more interest. "There are still two paintings left that you have not explained," I said, "and yet I would have thought that we had reached the end of it. Where can you go beyond a life of active virtue and apostolate?" "You can go to the heart of God himself, loved for his own sake. The fifth medallion represents the existence of the One God, as revealed to Moses, and the sixth represents the Trinity, the central revelation of the Gospel. This is what theologians call the contemplative life," Michael concluded, "where God is loved directly for himself, and not indirectly through the things he has made, and that are more immediate to your senses." "Does the series represent a kind of progression, then?" I asked. "The first two are a preparation for conversion, the second pair represent the active life, and then finally, the contemplative life?" "You could see it that way," he replied. "But it would be more accurate to compare them to the rungs of a ladder rather than to a progression along the ground. The upper rungs of a ladder are supported by the lower, and the lower maintain their position because the top of the ladder rests against the wall. Nothing is outgrown or left behind. You can see this in the lives of the great saints; the deeper their love for God as he is in himself, the more effective their love for him in their creation. Some of the greatest contemplatives have spent their lives working for justice, and as for the love of nature, you need only consider the work of the Benedictines in agriculture, and of all the schools and hospitals established by Christians in every country." "Are the six stages described in St. Bonaventure's book?" I asked. "Yes, and he has a seventh to complete them." "But there are only six medallions," I pointed out. "Where is the seventh?" "Straight ahead," Michael replied, pointing to the mural behind the altar. "Recall that the seraph appeared to St. Francis in the form of the Crucified, not in the form of a theological treatise." I let this pass, since I was still struggling with the earlier stages. But while my intellect grappled with the words I had just heard, some deeper change was taking place at the level of the imagination, where so many of our prejudices are formed. Perhaps had I read Bonaventure's book on my own, his Medieval zeal for cross-classification and symbolic symmetry might only have re-enforced the usual divisions between sacred and secular, active and contemplative, lay and religious, that give the typical lay Catholic his defence against sanctity and the untrammelled love of God. But hearing the doctrine from Michael, a creature innocent of the divided heart, I could see the unity underlying the distinctions. Barriers fell. The plaster saints of false piety shattered and were still. Suddenly, I understood the distinctions of the Medieval doctors for what they were: diagnostic tools for the doctor of the soul, to be placed in the service of the love and knowledge of God. Distinctions were made, not to divide, but better to appreciate the power of God in each. "But this is extraordinary," I said at last. "If what you are saying is true then everything is prayer, even ordinary work!" "Explain," said Michael. "Yes," I said, in swift pursuit of the insight that had glowed momently in my mind. "To pray is to raise the heart and mind to God. Is that not so?" "An adequate definition. Well?" "Well, according to Bonaventure we perceive God even in ordinary material things, so when we work with them, we are, in a sense, facing God. The mind can always be raised to God, either directly in prayer, or indirectly through our dealings with other people and nature. There is no essential difference between the active and the contemplative lives, since there is only one vocation, which is to love God." As I was making my explanation, I noticed that Michael seemed to be gathering himself inward under pressure of an ever deeper concentration of prayer. "Yes!" he said, and the little word seemed both to ring in triumph and to hold its breath in expectation. It was very still. "Now," he continued, "you said that prayer was the raising of mind and heart to God. Where does the heart fit into your scheme?" "Oh." I said. "I don't know. Did I say something brilliant just then?" "No. Only something obvious: that to perceive God through ordinary things is to pray. Now take what you said about the knowledge of God and apply it to the will. Do what you do for God, and you will turn your actions into prayer as well." It was that simple. But then I looked past the archangel to the great mural at the front of the chapel, and thought of Francis and the striking austerities of his life. "Can one be a saint without living like Francis?" I asked. "Is it possible to avoid all those ... austerities?" "That sounds like the question of someone trying to get out of some hard work," said Michael. " "No, it isn't," I said. "Well, perhaps it is. It's just that no one could hold down a full time job while living as Francis did, so what hope does that leave for the rest of us? And if God is as close to ordinary things as you seem to suggest, why the need for such a desperate struggle?" "Ah!" said Michael in reply. He opened his hands in a shrug as if to suggest that the contents of the chapel were explanation enough. "I am surely among those in the created universe least suited to answer your question," he said at last. "But let me at least tell you this much. First, from my own experience, I can tell you that sanctity is profoundly natural, in the sense that it is precisely what you, and everything you are, body and soul, is longing to be. If everything you did was done for love of God, with nothing superfluous or merely private, then you would be holy. It is not austerity that makes for holiness, but love. "But secondly, given that your nature has been spoiled by sin, for you, putting God first demands a constant struggle in putting yourself last. This they call dying to self, and from what I have observed, dying is not too strong a term. And thirdly, when your love for Jesus grows, along with your compassion for the many souls that do not know him, you will want to share his sufferings. And on that day, you will be glad to have suffering to offer." "One thing I don't understand," I said in unwitting understatement, "is why it takes so long. I can see how there should be gradual improvement toward sanctity if it were only a human activity, but since it is God's work, why doesn't perfection follow immediately upon conversion?" "A good question. I have never understood it myself, although the truth of it is constantly before my eyes on Earth, and the results are evident in Purgatory. I can understand saying 'yes' to God, and I can almost see how one might say `no'; but to say 'wait!' or 'Yes, but ...' There you have the mystery of the human race, and it is a constant source of amazement to the rest of us. "Basically, the burden of the ascetical struggle is to turn that 'wait' into a 'yes, but'; then to get rid of the 'but.' It is not something to be attempted on one's own, if at all possible. You might want to call Fr. Francis Fitzgerald, the chaplain here. He has helped many waverers to get off the fence and serve the Lord in earnest." As if to illustrate this point, Michael rose to his feet and stood between the rows of chairs as if ready to go. I stood up to join him, but he motioned me away. "Go with God," he said and disappeared. I returned to my knees, and for a long time no thought entered my mind. I looked to the Tabernacle, but its faithful guardians were visible to me no more. The Heavens were closed again; no trail of glory remained to mark the spot. After a while, I noticed a presence to my left. I looked up and saw a man standing at the end of my row, short, wiry, middle aged, and wearing the Franciscan habit. "I am Fr. Frank," he said. "Can I help?"

This book is reproduced with the author's permission. Copyright © Catherine Dalzell 1995, 2009 All rights reserved Illustrations Copyright © Gordon Gillick 1995

Version: 3rd December 2009 |