|

Thursday’s Father

The cosmos in the mind of G.K. Chesterton.

by Dawn Eden

G.K. Chesterton, Theologian by Aidan Nichols

Second Spring, 240 pp., $19.95

uk publisher of this book, Darton, Longman and Todd.

It is said that the study of metaphysics is dying because people no longer want to study things

that cannot be changed. One sees this in the popularity of the Serenity Prayer, in which the thing most feared

is not, as with the Lord’s Prayer, the temptation to sin, but rather the inability to control one’s circumstances:

“God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change.”

Had G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) lived to read the Serenity Prayer (it emerged shortly after his death), he would

have found it ironic that the orison earned fame as the mantra of the recovery movement. Coming of age in an era

when preening poets went Wilde wearing carnations the color of the bilious liquor they imbibed, Chesterton recognized

early on that the true subversion was sanity. “Revolt in the abstract is—revolting,” says his protagonist Gabriel Syme in The Man Who Was Thursday (1907). “It’s mere vomiting. . . . The most poetical thing in

the world is not being sick.”

Such an appreciation of the artfulness of “things going right” characterizes the brand of metaphysical realism that Aidan Nichols, the English Dominican priest and

prolific author, identifies as central to Chesterton’s worldview. In G.K. Chesterton, Theologian, he traces the

origins of that realism back to the literary giant’s personal background and his reactions to the leading cultural

figures of his time. Nichols’s Thomistic talent for systematizing leads him to find connections between Chesterton’s

use of paradox, his demonstration of God’s existence (the “argument from

joy”), his understanding of man as imago dei, and his Christology.

While his subject has been called The Apostle of Common Sense, Nichols stresses that “metaphysical realism is not merely the upshot of a commonsense epistemology.”

It is also “the fruit of the doctrine of creation, which declares things

to be intelligibly planned by the divine mind who called them ‘good.’” As Chesterton

wrote in a 1910 essay,

The primordial things—existence, energy, fruition—are good so far as they go.

. . . The ordinary modern progressive position is that this is a bad universe, but will certainly get better. I

say it is certainly a good universe, even if it gets worse.

From this core philosophy, Chesterton, in his 1908 classic Orthodoxy,

was able to critique the “madness” of his “thoroughly worldly” contemporaries. Their errors stemmed not

from irrationality but rather from the narrowness of the data they admitted into the realm of reason, as Nichols

observes:

Within their own limited terms of reference, lunatics are often cogently rational.

. . . Chesterton takes the mark of madness to be the “combination between a logical completeness and a spiritual

contraction.” Madmen are in “the clean and well-lit prison of one idea.”

In modern terms, he saw the prominent scientific rationalists of his day, as well as modernist Christians (“new theologians [who] dispute original sin”), as conspiracy theorists—the

intelligentsia’s equivalent of the black-helicopter/tinfoil-hat crowd. While his arrows were aimed at contemporaries

such as George Bernard Shaw and Ernst Haeckel, one does not have to look far to find modern-day examples of the

blinkered mindset he describes: Witness Richard Dawkins saying that he would cling to his nonbelief in God even

if it meant having to posit that an outer-space alien designed human life. Chesterton is seen by many as an answer

to such New Atheists because, in Nichols’s words, “metaphysical realism,

as an account of cosmic order hospitable to the Christian doctrine of creation, can improve on the materialist

account: Whereas Christians are free to believe that there are large areas of ‘settled order and inevitable development’

in the universe, materialists, Chesterton points out, cannot allow the slightest incursion of spirit or miracle.”

Still, despite the New Atheists’ media stardom, the most popular modern heresy, at least in terms of book sales,

is not materialism but solipsism—the Me-centered philosophy of Oprah, Chopra, The Secret, etc. While New Atheists see the New Age movement as merely a subset of religious superstition, Chesterton

saw the solipsism of his day—and the Kantian subjective turn that provided it with its pseudo-philosophical ground—as

the flipside of materialism. The two “have something in common,” Nichols writes, quoting from Orthodoxy: “The man who cannot

believe his senses, and the man who cannot believe anything else, are both insane, but their insanity is proved

not by any error in their argument, but by the manifest mistake of their whole lives.”

One is reminded of the solipsistic science-fiction author Philip K. Dick who, when asked by a college student in

1972 to give a definition of reality, gave a purely negative reply: “Reality

is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” By contrast, Chesterton

counters both the narrow negativism of solipsism and the equally narrow perspective of what modern materialists

call the “reality-based community,” as he insists

“reason is itself a matter of faith.”

Nichols explains, “Naturally, by ‘faith’ here Chesterton doesn’t mean specifically

Christian faith. He is speaking of a philosophical faith grounding confidence in the fundamental reliability of

the human mind and its most refined instrument, which is language.” Both materialists

and solipsists share an odd collective aphasia. In their refusal to accept the Word that transcends everything

men can know, they deny the means by which men can know anything.

Nichols details how Chesterton’s desire to harmonize faith and reason eventually led him to St. Thomas Aquinas.

His 1933 biography of the saint “follows the movement of Thomas’s own thought

as it finds in the finite being presented through the senses a way to the fontal being which pours itself out in

all that is.” But Aquinas was more than a philosopher; he was also a mystic. Chesterton

understood him because he shared his sense of the numinous. An analysis of Chesterton’s mystical insights would

support Nichols’s assertions that his theology speaks to today’s Christians.

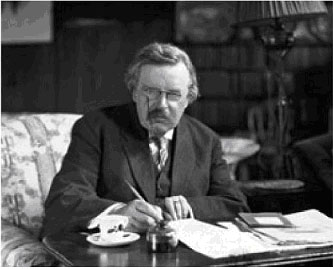

G.K. Chesterton, ca. 1920

Nichols, however, is by his own admission “not. . . .

a mystic,” and this limitation occasionally leads him to an un-Chestertonian closed-mindedness.

For example, he omits any mention of the 1907 “Introduction to the Book

of Job”—the closest Chesterton ever came to biblical exegesis. Likewise, he gives short

shrift to his subject’s most profound novel, The Man Who Was Thursday, a work whose theme of theodicy built upon the points Chesterton made in his Job essay—particularly his

observation that “the riddles of God are more satisfying than the solutions

of man.” In his curt comments on Thursday,

Nichols claims,

The key to that novel is that the men who represent cosmic order in society

are pursued, harried, by those who suppose them to be really anarchists. In this way, the representatives of order

who police the world for its health and safety are able to bear witness that they too have suffered, and this gives

them a moral cachet in the eyes of all who consider themselves the victims of order.

But that is not quite true. The sufferings of the policemen in Thursday are not for the purpose of giving them cachet in the eyes of the story’s lone “real anarchist,” Lucian Gregory. Rather, they exist so that the believer

might use his God-given free will to unite himself to Christ, whose victory comes through suffering, and thereby

reject the lies of the original anarchist, for whom the similarly named Lucian is a mere stand-in.

Nichols’s avoiding extended analysis of Thursday is all the

more strange because the book’s true message actually affirms his grammar of Chesterton’s theology. In fact, G.K. Chesterton, Theologian is extraordinarily valuable precisely because Nichols’s

grammar, applied to Thursday, not only brings the novel into

fuller focus, but also reveals the prophetic quality of Chesterton’s religious understanding. For example, he rightly

draws the reader’s attention to the way Chesterton marries his metaphysical realism to his appreciation of symbol

as “an equally far-reaching way of displaying what is involved in the real.” In The Everlasting Man, Nichols writes, “the Incarnation of the Word makes possible precisely such a union . . . . [linking] a universal

philosophy that abstracts from concrete things in the search for general and underlying structures, on the one

hand, and on the other, a mythopoetic imagination that discerns divine presence and action as the matrix of the

most important concrete things.”

Such an observation adds depth to the epiphany of the Thursday

protagonist Gabriel Syme, who intuits that all visible creation is sacramental—real in itself, yet symbolic of

an invisible reality that is personal:

“Listen to me,” cried Syme with extraordinary emphasis. “Shall I tell you the

secret of the whole world? It is that we have only known the back of the world. We see everything from behind,

and it looks brutal. That is not a tree, but the back of a tree. That is not a cloud, but the back of a cloud.

Cannot you see that everything is stooping and hiding a face? If we could only get round in front—”

This message is far more pertinent to Thursday than Nichols’s

purported “key to that novel.” Omitting it, he

misses an opportunity to show how Chesterton presages the similarly sacramental account of creation that Pope John

Paul II would give more than 70 years later in his addresses on the “theology of the body.”

In “the mystery of creation,” John Paul said,

the world began “by the will of God, who is omnipotence and love. Consequently,

every creature bears within it the sign of the original and fundamental gift.” In a joyful

paradox that would not be out of place in Orthodoxy, the pope

adds that this gift is centered upon man: “Man appears in creation as the

one who received the world as a gift, and it can also be said that the world received man as a gift.”

Despite overlooking this affinity between Chesterton and John Paul, Nichols’s grammar leads to a deeper understanding

of both. He highlights a passage from Orthodoxy describing how

“all creation is separation”: “It was the prime philosophic principle of Christianity that this divorce in the divine

act of making . . . was the true description of the act whereby the absolute energy made the world.” John Paul drew upon the same point in his theology of the body to show how, in the Genesis creation

accounts, man’s ability to give himself in love is contingent upon his realization of his “original solitude”—the “separation” of which Chesterton speaks, which, in the late pope’s words, “permits

him to be the author of genuinely human activity.”

The first man’s recognition of his solitude is linked, John Paul says, with his recognition of his “dependence in existing” in which he faces, for the first time,

the “alternative between death and immortality.”

For Chesterton, such “isolation” marks the “root horror” endured by Thursday’s Syme. As John Paul notes, however, it is only through recognizing one’s self as having a separate identity

that true interpersonal communion is possible: “In this solitude, [man]

opens up to a being akin to himself.”

Here too, Chesterton seems to be completing John Paul’s sentences, as he writes of Syme’s joy in discovering that

one of his seeming enemies is actually a fellow policeman: “There are no

words to express the abyss between isolation and having one ally. It may be conceded to the mathematicians that

four is twice two. But two is not twice one; two is two thousand times one.” But Chesterton’s

next line in some sense even surpasses John Paul because it shows what he had that the theology of the body, for

all its genius, utterly lacked—humor: “That is why, in spite of a hundred

disadvantages, the world will always return to monogamy.”

Shortly before his death, Chesterton wrote that one of his favorite tributes came from a thoroughly secular psychoanalyst

who told him, “I know a number of men who nearly went mad, but were saved

because they had really understood The Man Who Was Thursday.” There’s serenity for you.

Dawn Eden is the author of The Thrill of the Chaste: Finding Fulfillment While Keeping Your Clothes On.

Copyright 2010 Weekly Standard LLC.

This article first appeared in the (August 30 - September 6, 2010, Vol. 15, No. 47) issue of

The Weekly Standard and is reproduced with the publisher's kind permission.

Version: 7th September 2010

|